NoCo Science Education Blog: Collecting Rain, Collecting Data, and Collecting Scientists with Nolan Doesken and Noah Newman

By Victoria Jordan

Station reports from the CoCoRaHS website:

“KY-LG-10 (12/13/2021)- Community trying to recover from Sunday morning tornado. Lots of damaged trees down, barns destroyed, houses damaged with roofs blown off, garage doors buckled, trees on cars, and houses, travel trailers and motor homes blown over. Probably excess of 100 fatalities – 10 known in joining county. A mile of 3 phase electric lines down-poles twisted and snapped.”

“Dear CoCoRaHS,

My home was destroyed in the recent tornado in Kentucky. My rain gauge vanished like Dorothy’s house. I will have to stop reporting my data for awhile.”

What IS CoCoRaHS?

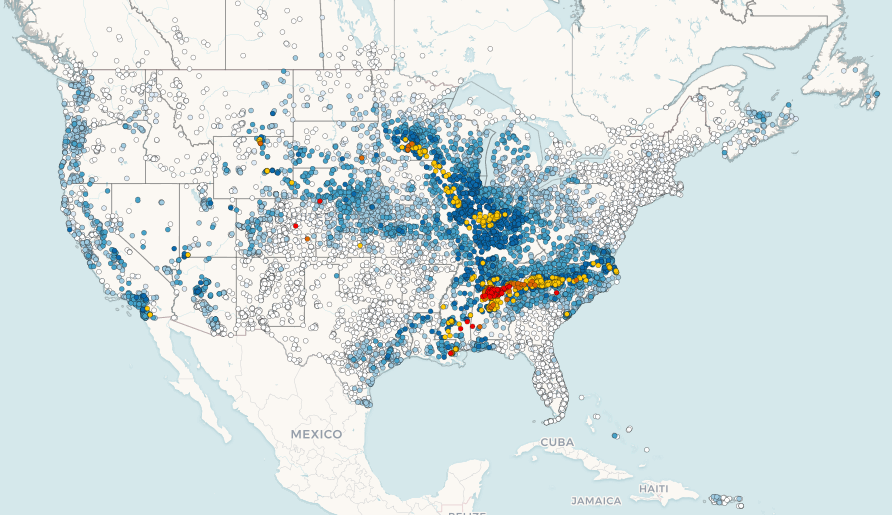

CoCoRaHS is the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network. It is a non-profit, community-based network of volunteers who measure and report rain, hail, and snow in their backyards. CoCoRaHS is the brainchild of Nolan Doesken, retired Colorado State Climatologist. You can read more about the history of CoCoRaHS, check out the data, maps, and educational materials here: https://cocorahs.org/

What CoCoRaHS really is goes beyond the network of over 25,000 volunteer reporters from every State, Canada, Puerto Rico, Bahamas and the Virgin Islands, and its hundreds of users of the data, including The National Weather Service, other meteorologists, hydrologists, emergency managers, city utilities (water supply, water conservation, storm water), insurance adjusters, USDA, engineers, mosquito control, ranchers and farmers, outdoor & recreation interests, teachers, students, and neighbors in the community. Yes, it is all that. But, what cannot be captured in the data is the teamwork, collaboration, and sense of community that brings people together in this seemingly simple citizen science program.

“Nothing I have ever done has resulted in so many friendly collaborations, all with just a simple backyard rain gauge!” says Nolan Doesken, the charismatic founder and backbone of the network. “Our youngest volunteers are 4-5 years old (with parental help), and our oldest is 103.” Nolan writes personal welcome letters to at least 20 applicants each month, and his newsletters contain both scientific information and personal notes about life on the farm that keep volunteers begging for more.

“Dear CoCoRaHS,

My husband recently passed on. For the past many years, he got up every morning at 6:45 so that he could check the rain gauge and report his data. You kept him going. Now, my children want to take the gauge and teach their children how to report data and maintain a connection with Grandpa. How can we transfer his account over to them?”

CoCoRaHS Creates Scientists

As volunteers enter their data, they have an opportunity to comment.

“AL-MG-17 (09/19/2021) – Rain continued throughout the night. The air is humid but cool this morning. Interestingly, we have 5 garden spider webs around the house. The most before was 2. They all appeared over just the last week or so.”

CO-LR-676 (03/15/21) – 1.62” moisture, snowpack depth 26”; The new snow amount is just an estimate because of drifting. It is likely more due to compacting. I had to go out a window to get to the rain gauge. Snow blocked the door.

“It amazes me how dedicated people are to the process,” says Noah Newman, education specialist with CoCoRaHS. One person wrote that CoCoRaHS is helping them stay sober with their AA commitment because they can’t get up to check the rain gauge at 7:00 am if they are hungover. When Nolan and Noah were trying to fill in some blank spots on the map by recruiting volunteers, one observer told them, “Come on over for dinner. I’ll put you in touch with our County Commissioner.”

One of the highlights for Nolan was when the White House installed a CoCoRaHS gauge in Michelle Obama’s White House garden, and staff members were reporting the new station data. The Washington Post used their data in their daily weather reports while the station was operated. Nolan was honored at the White House science fair reception that year, and was photo-bombed by Bill Nye!

Noah works with K-12 schools across Colorado and the nation to develop lesson plans that allow students to become scientists. “I have many star teachers that have students report data throughout the school year, and some kids end up starting a station at their house. One particular teacher works at a juvenile detention facility in Oregon. The kids are so proud to be able to report data and learn atmospheric science. One graduate used his CoCoRaHS certificate to help him land a job as a forest firefighter.”

Motivation

CoCoRaHS has one of the largest volunteer networks of any citizen science program. With a 60% retention rate, they rank among the top programs in the nation. Consistency with the staff over the decades has been a key component to the success of the program. In a recent study to determine what motivates volunteers to continue reporting, many people commented on the value Nolan brings to CoCoRaHS.

“I’m reporting data because I was asked to do it by Nolan.”

“My brother roped me in, and I just keep doing it because I’m reminded in the newsletters and blurbs on the site how important the data is.”

“I love Nolan and his newsletter!”

Noah adds that, “CoCoRaHS is a bit ‘gamified’ because each rain event is different, every day the map looks different, and it builds curiosity.” Reporting really took off during Covid because people were stuck at home. “We provided a way for people to be involved in their community in a positive manner, doing something that actually matters.”

What About the Data?

“Without CoCoRaHS, we would not have neighborhood-scale data,” Nolan says. Precipitation is so variable in the span of neighborhoods, that the goal is to have one rain gauge every square mile in urban and one every 36 square miles in rural areas across the nation. “One unique aspect of having this much coverage means that we can replace time with space to gather enough data to adjust historic averages,” Nolan adds. They have done statistical analyses in several parts of the country, and have found that if they have 10 or more volunteers reporting regularly in a 10 mile radius, they only need 2 years of precipitation data to equal the value of 100 years of data from a single “official” weather station. “It doesn’t line up quite right on the extreme ends of the data,” Nolan clarifies, “but, for things like the historic averages and 100 or 500 year weather events, it works great.”

When NASA was still launching space shuttles, they needed to find a way to figure out if hail was damaging the tiles on the shuttle while it was sitting on the launch pad. CoCoRaHS to the rescue! The hail pads that are used, simply heavy-duty aluminum foil covering a square of 1” Styrofoam, are able to record enough data in a hail event to allow scientists to determine whether the shuttle can fly. Insurance companies can use the data to determine car and roof damage, as well.

Quality Control of the data is a big concern, and a lot of manpower is put into ensuring that volunteer data is reasonable and accurate. Coordinators throughout the nation monitor State data, and continue to educate volunteers whenever they notice mistakes. “We have an endless supply of new people who make the same old mistakes,” Noah says. “Data entry has decimal point mistakes. Snow depth gets tricky with wind and drifts. People often read their gauge correctly but enter the wrong day or time.”

“We are in an interesting time, with everything going digital,” Nolan says. “Raindrop spacing, drop size, wind all make a difference to the catch. But, what we have found over the years is that our CoCoRaHS rain gauge provides the most accurate data of any type of precipitation measurement device.” He is hopeful that the new generation of scientists and volunteers will be committed to continuing to use the manual gauge. “Being out in the weather allows people to have a rich experience. Every drop counts.”

You can count, too. Visit the CoCoRaHS website https://cocorahs.org/ to purchase a gauge, apply for a station number, find lesson plans, attend an online or in person training, make a donation, and study the maps. Join the CoCoRaHS Juggernaut!

Listen to the original CoCoRaHS song by Dewey Longuski and lyrics by CoCoRaHS volunteer Ann Donoghue (CO-LR-36):

https://media.cocorahs.org/video/ComeHailOrHighWater.mp3

NoCo Science Education Blog: Decades of Discovery – Explorations with Dr. Stephen Thompson

By Victoria Jordan

Dr. Stephen Thompson, Explorer

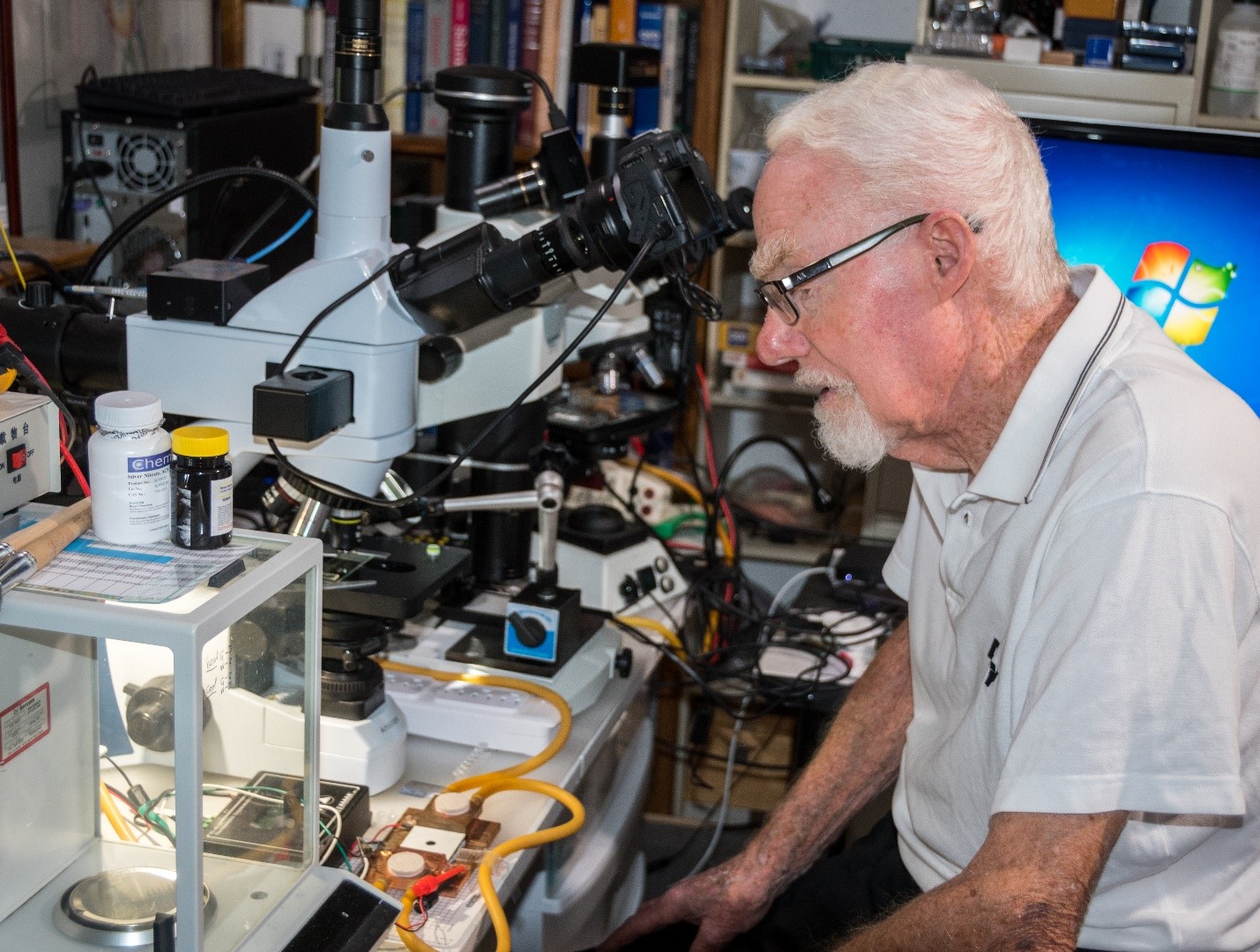

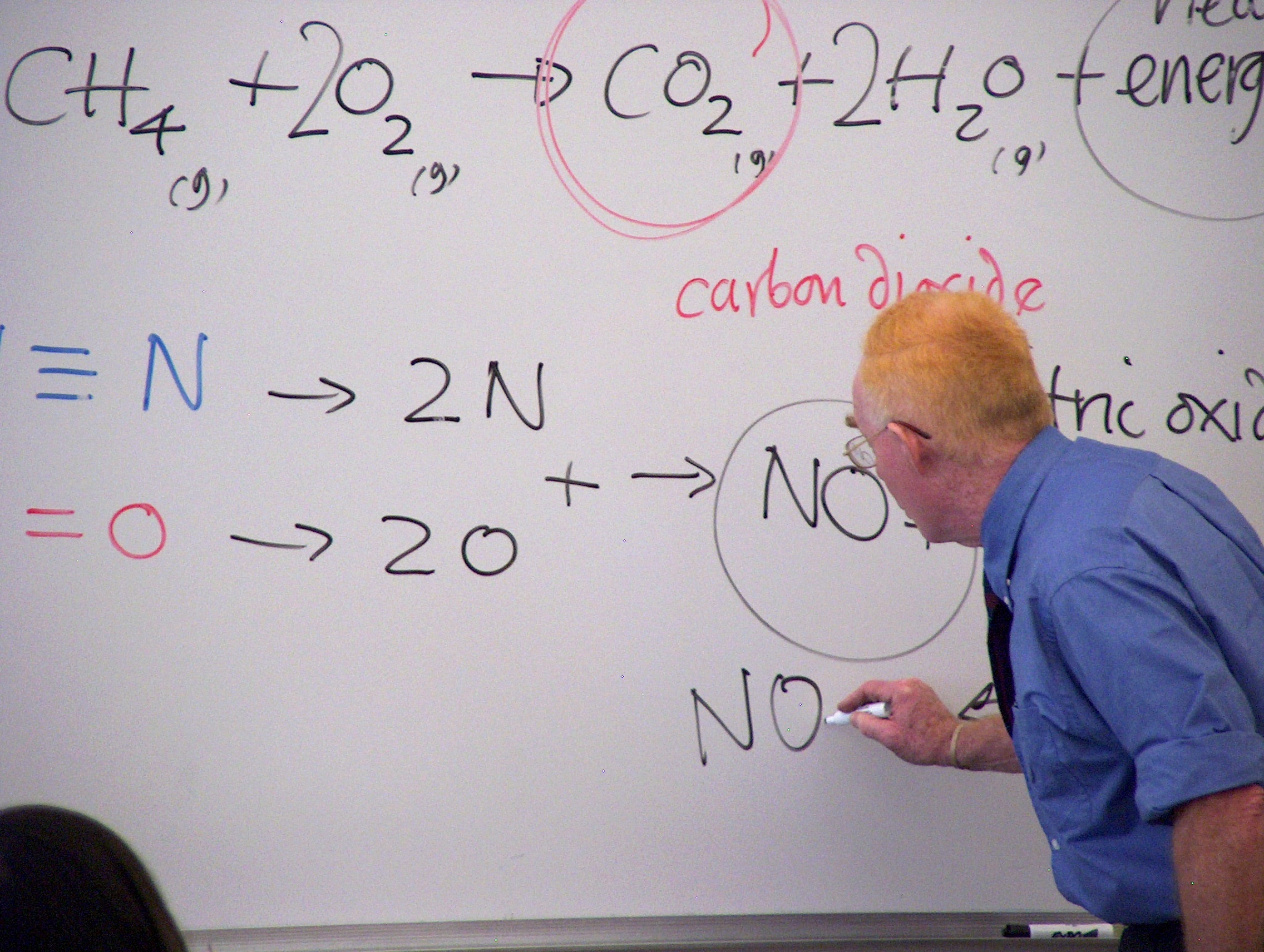

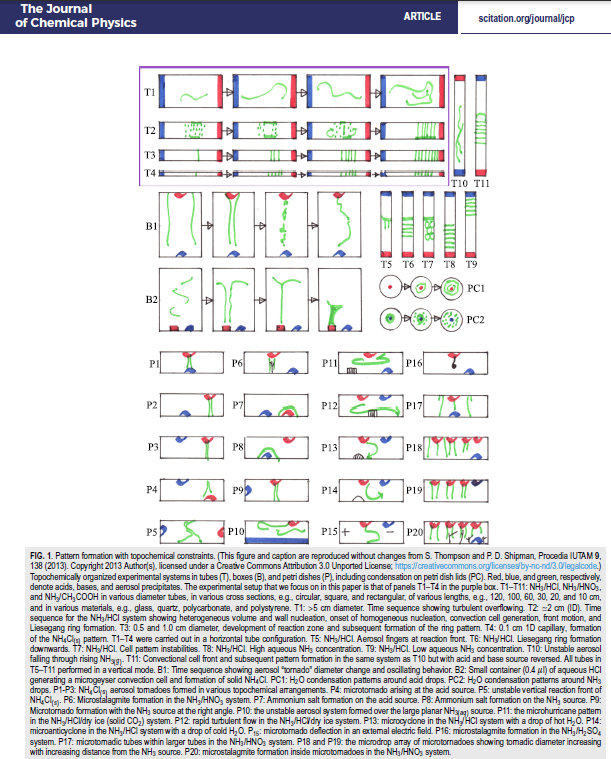

Microtornadoes, microstalagtites, and microhurricanes are beautiful 3-dimensional gaseous structures created by chemical reactions in Dr. Stephen Thompson’s laboratory. In order to facilitate his explorations of molecular fields, Dr. Thompson built microscopes himself that include high resolution video with fiber optic connectors and various lasers to study chemical reactions on the fly as they take place.

Microscopes

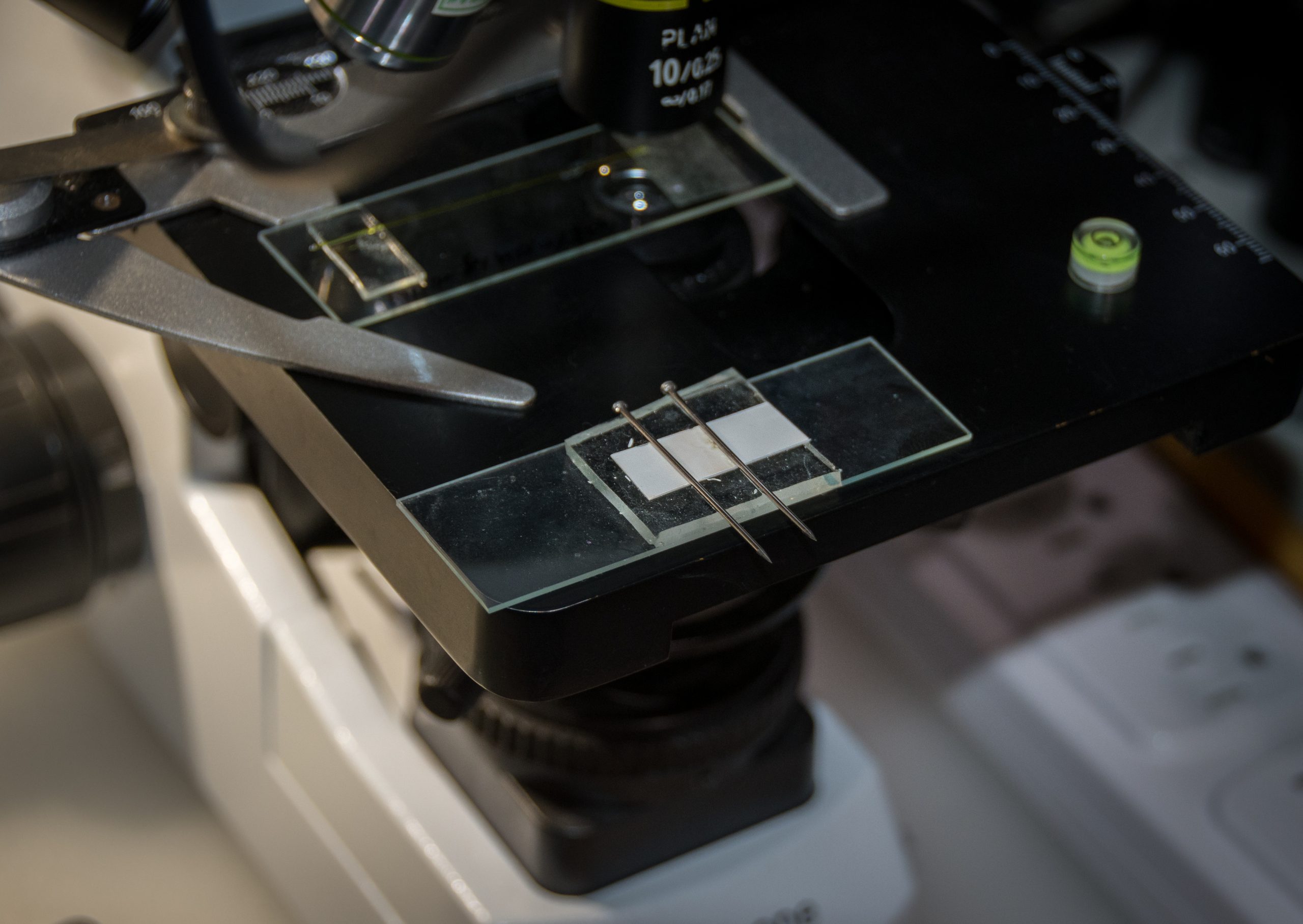

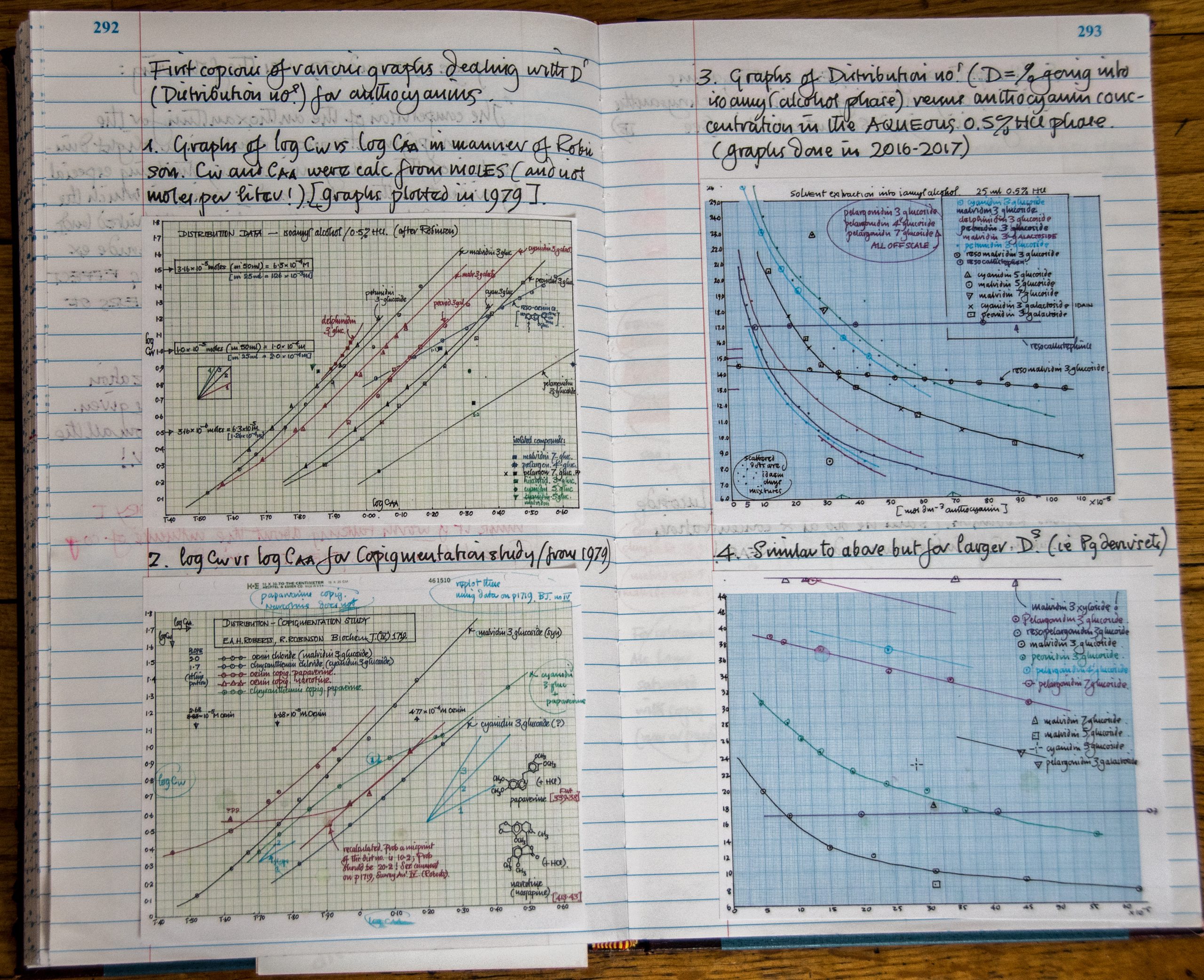

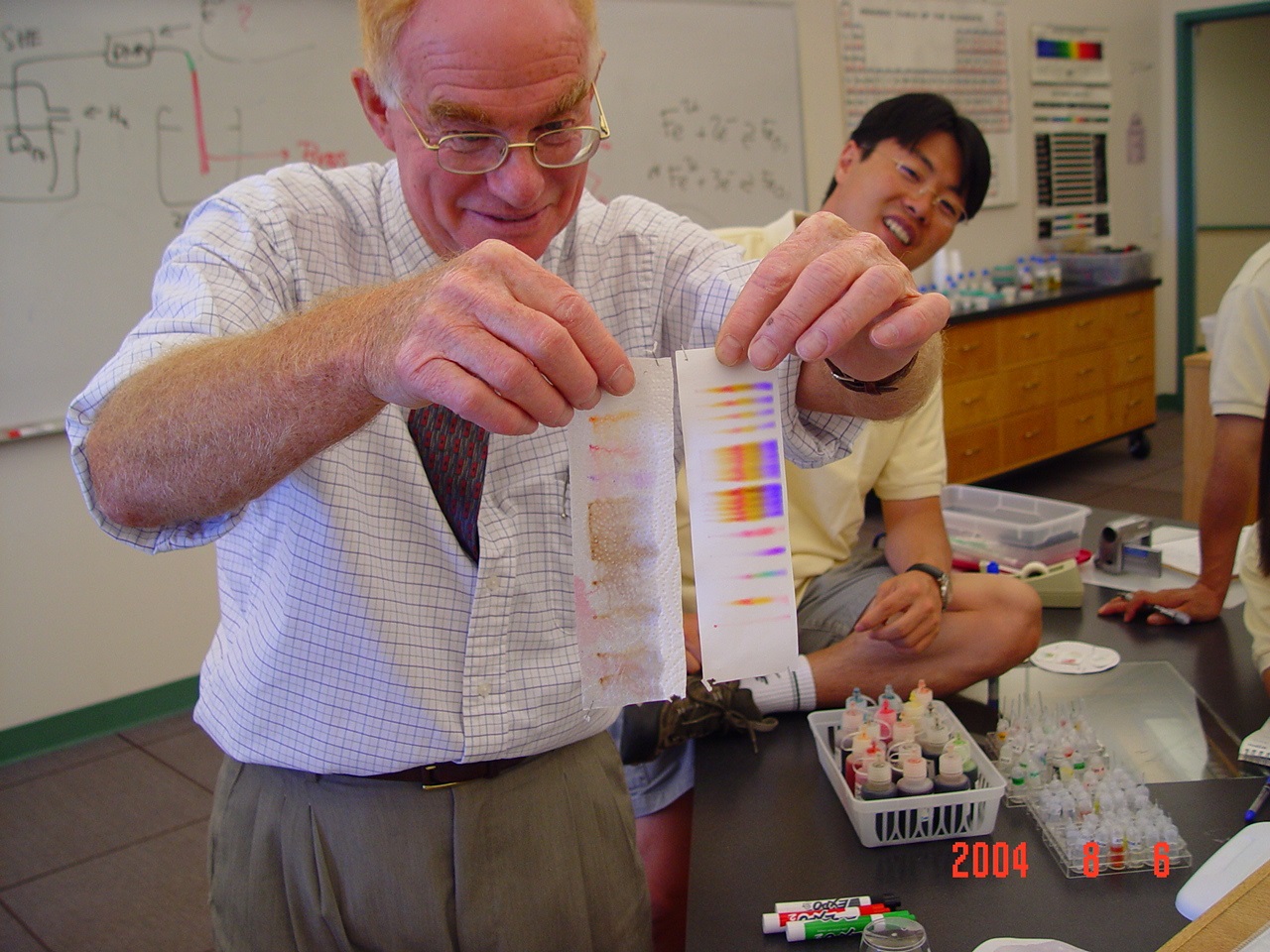

He is exploring anthocyanins (colorful plant pigments) using spectroscopy and chromatography to find mathematical patterns. He is conducting microfluidic electrophoresis of anthocyanins by taping sewing pins onto a microscope slide so he can watch and film the process as it happens under the microscope.

Dr. Thompson is using capillary tubes to view aerosols for experiments with colored lasers, transferring large scale experiments to small scale where the observations can take place on a molecular level. His passion for exploration is never-ending.

Small Scale Chemistry

Dr. Thompson is best known for his groundbreaking development of Small-Scale Chemistry to promote student-centered inquiry in college level chemistry classes. In the 1990’s, he co-wrote a grant to create the Center for Science, Mathematics and Technology Education (CSMATE) at Colorado State University, and helped to design a modern college experiential studio where he utilized Small Scale Chemistry methodologies that encouraged students to learn science by doing science. Thompson shared his educational philosophy through the lens of Small-Scale Chemistry to K-16 public school teachers by offering numerous professional development courses funded by the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency and others. The collaborative partnerships’ that Thompson nurtured with public school teachers helped to transform the way an entire generation of science teachers and their students experienced learning and exploring science.

Tim Lenczycki, a high school chemistry teacher, is one of many teachers that have adopted small scale practices. Tim says, “Dr. Thompson is not only a spell-binding lecturer, but his expertise as an educator really shines one-on-one. He truly finds importance in student opinions and honestly values their insights. He empowers students in their own knowledge and skillfully leads them to higher levels of understanding. I have not met a person who is more well-read than Steve Thomson. Coupled with his vastly varied other pursuits, he is an authentic renaissance man.”

Dr. Thompson attempted to influence University science education away from the business model where hundreds of students can be packed into a lecture hall to more of an experiential model in which students could scientifically explore natural patterns with guidance from the instructor. In Thompson’s model the teacher takes on the role of mentor, thus learning becomes a partnership with his students. His college text, ChemTrek, has been translated into several languages, and is used extensively in Asia. Thompson has carried out workshops in Korea, Japan and Thailand to broadcast small scale approaches across the globe.

The value of Thompson’s Small-Scale Chemistry methodologies are even embraced by schools that have not had the opportunity to learn his student-centered pedagogy. “Asian schools doing chemistry who were using traditional methods of teaching were generating large amounts of hazardous waste, and they adopted Small Scale Chemistry in order to solve some environmental problems they were having with hazardous waste management in schools and universities. It also happens to save millions of dollars,” Steve says. Small Scale Chemistry allows every student to design and carry out their own experiments using multiple iterations, partly because there is little waste and a huge cost savings. Additionally, Small Scale Chemistry is much safer than traditional chemistry labs that use large glassware and high volumes of potentially dangerous chemicals. Dr. Thompson earned recognition for eliminating accidents in the lab during his tenure at CSU.

Every teacher who has gone through one of Steve’s trainings takes away the importance of student exploration and engagement. A Thompson lesson typically starts with introducing students to a natural phenomenon, which is followed by guided exploration and finally open inquiry. This process nurtures a student’s ability to discover natural patterns by asking questions and designing experiments. The hands-on approach also encourages students to think critically about what they claim as knowledge. “How do you know that?” is one of Steve’s mantras. Getting students to think, to ask questions, and to try to find answers is his forte. “Small scale isn’t just about reducing the size of the experiment. It’s about how teachers and students approach the learning.”

On the Shoulders of Giants

Dr. Thompson surrounds himself with inspiration, and has a very extensive private scientific library. “I am a student of the history and philosophy of science,” he says. “I have every book written on the history of laboratories, and I have an incredible collection of books regarding women in science, astronomy, biology and chemistry. Scientists are people with stories, and I want to know who these people were.” For example, a German scientist, Rafael Liesegang, wrote a paper in 1896 about diffusion gels. Thousands of people reference this work, but very few have ever studied it directly. During the Covid lockdown, Steve translated all 53 pages from the original German to English. Thompson and colleague Dr. Patrick Shipman are extending Liesegang’s work and developing mathematical models for the pattern systems from that original work.

When Steve looked at the literature from the 1890’s regarding the chemistry of anthocyanin pigments, he analyzed the works of 2 Nobel scientists: British organic chemist, Sir Robert Robinson and a German chemist, Richard Willstatter. Steve found that Willstatter grew flowers by the acre in Berlin and extracted the anthocyanins to analyze their structure. Steve is exploring the concept that anthocyanin associations influence flower color, odor and pollination ecology, and has assisted graduate students including Dr. Wei Yu who recently completed a thesis project on this topic. Steve has taken all the data he can find in the literature, plus his own data, and is coming up with new conclusions and new experiments.

Steve’s work on teaching the chemistry of climate change has been inspired by his favorite chemist, John Tyndall. In an 1880’s book Heat: A Mode of Motion, Tyndall explored climate change by examining the transmission of energy in the form of heat. Steve has taken Tyndall’s original experiments and is translating them to a small-scale version using micro-encapsulated liquid crystal mylar systems to model and explore energy transfer.

Dr. Thompson is never alone in his lab. He always brings scientists past and present into his work. Currently he is working with 2 graduate students as they complete research projects. One is examining the fundamental chemistry of why sinkholes are forming in Horsetooth Reservoir. The other is exploring anthocyanins as phytophoto protection for newly forming organelles in plants. Dr. Thompson loves being a researcher and a teacher, and has no plans to stop doing either.

From Then to Now

Born in a small mining town in northern England, Dr. Thompson earned his PhD from the University of Birmingham, England. From there, he dropped out of academia to grow bananas and play tennis on St. Vincent in the West Indies. When he decided to re-enter society, he came to America on a post-doc fellowship to the University of Arizona in Tuscon, and then became an Assistant Professor at the Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland. When a professor at Colorado State University saw him eating fire at a demonstration in 1969, he reached out and said, “I think you would be a great teacher in our freshman courses,” and Steve never looked back.

Dr. Thompson claims his methods are not special. “If you want to find out what’s going on, you have to start with what you know. All we do in science is take something we don’t know anything about and put it next to something we know something about and find the similarity.

The history of science is really the history of containers,” he claims. When he first started teaching chemistry at CSU, everyone was using large amounts of chemicals in large containers to prove a concept. “Now that we are working on the molecular level to explain and prove concepts, we can use very small amounts of materials in very small containers. Take a drop of water. In that drop, there are billions of molecules to study!” Steve exclaims.

True to his nature, Thompson studied another English scientist, Michael Faraday. Faraday viewed chemical reactions as molecular fields in the early 1800’s. Small Scale Chemistry came out of the methodologies Faraday used as an experimenter, and Steve’s perusal of Faraday’s notebooks helped him create his methods. A S3TAR was born. The S3TAR (Small Scale Science- Teachers As Researchers) program brought together middle and high school science teachers to learn Small Scale methodologies in summer programs, and those teachers went on to train their departments, influencing an entire generation of science teachers.

The Future

Smart Scale Sustainable Science and Mathematics (S4M) is Steve’s latest iteration of how he would like to see science and math taught in schools. “The walls that separate the traditional sciences are beginning to crumble. The compartmentalization of the disciplines needs to go away, and mathematics, the language of science, is the thread that ties them all together.”

The pandemic brought to light all the failings of the educational system, and Thompson is currently researching better ways to get students to learn, to explore, and to embrace science and math. “The fundamental problem is that most classrooms are lecture-based. We need to infuse phenomena and exploration into every lesson. Experimental work is disappearing in classrooms, and I am hopeful that S4M can do away with lecture and provide ways for 100% of the students to engage in explorations of their world 100% of the time.” He is working on a book with the working title of Existential Education. In his 60 years of investigating chemistry and 40 years in education, Steve has continued to grow, explore and learn while inspiring teachers and students to do the same.

Stay tuned, as Dr. Stephen Thompson’s Opus has yet to be concluded.

See more of Dr. Thompson’s work at these links:

Thompson and Shipman’s paper in the Journal of Chemical Physics on the counterdiffusion of HCl and NH3

NoCo Science Education Blog: Make Learning an Adventure! with Mary Richmond

Engaging Teachers and Students with Authentic Field Work

By Victoria Jordan

Because I DID in Africa!

“That’s what field researchers would do!” science teacher Mary Richmond calls to her class as she coaches them to sketch macroinvertebrates from the Poudre River, collaborate about a plan for an experiment, and explore the school grounds to find a good place for a photo post. She should know. She IS a field researcher!

Ms. Richmond recognized that she wanted to infuse more authentic science experiences into her classroom teaching. So, when a National Science Foundation grant was awarded to CSU professor Dr. Randy Boone in 2011 to take a science teacher along to Africa to study wildebeest migrations, Mary applied and found herself cavorting with wildebeests.

She learned how to use telemetry equipment, collected plant and fecal samples in the field, and tried to figure out how roads and fences were affecting wildebeest migration. The Serengeti ecosystem of Kenya became her classroom for three weeks in the summer, and she was the student.

In excerpts from her journal, her wildlife encounters add up:

- As we drove down a desolate road, we found a leopard. It was in a tree, sleeping. Its paws and tail were hanging off the branches.

- We saw more giraffes, elephants, and hyenas. The local water hole we arrived at was a den of activity. Elephants were playing in the water, giraffes were on guard and under the bushes, on a rock wall were 2 lion cubs! Wow!

- I think Alfred got a little lost because we ended up in Tanzania. Oops! But we found the Mara River where we saw vervet monkeys, baboons, and hippos. The wildebeests will probably cross the river tonight or tomorrow morning.

Field research can be a messy business. It is experiences like these, however, that Mary could use to encourage her students to stick it out when the scientific process becomes challenging.

- Paul’s backpack got pooped on by vervet monkeys, and he had to change his shirt twice.

- We got stopped by the local conservancy wardens. We were not allowed to continue tracking the wildebeest in this area until we got permission from the head man.

- Dusty, dusty, dusty! My snot is even brown and Amboseli red.

- We started this morning searching for the wildebeest we could not find yesterday. We spent hours, and did not find him today, either.

The cultural experiences were equally enthralling. The research team stayed in a Masai village.

- Masai dancers greeted us at the entrance, and Masai people took our luggage to our rooms. I think they are half my size and two times stronger!

- Milk was warmed up over an open fire and diluted with water. Green tea in the milk, then strained and poured into metal cup. Served with chipati hot off grill.

- We had an interesting conversation with Sauna, Alfred, and Joseph about marriage, polygamy, and children.

- Swahili words: Asante – thank you; karibu – you’re welcome; simba – lion; mazongoo – white man

Forward-thinking Ms. Richmond had her Colorado students draw pictures of what their life is like, and contribute their favorite books to donate to a school in Kenya. When she visited the school in Kenya, the students exchanged pictures and books, and she brought a bit of Kenya back to her students in this manner.

Because Mary DID field research, her students see her as a scientist.

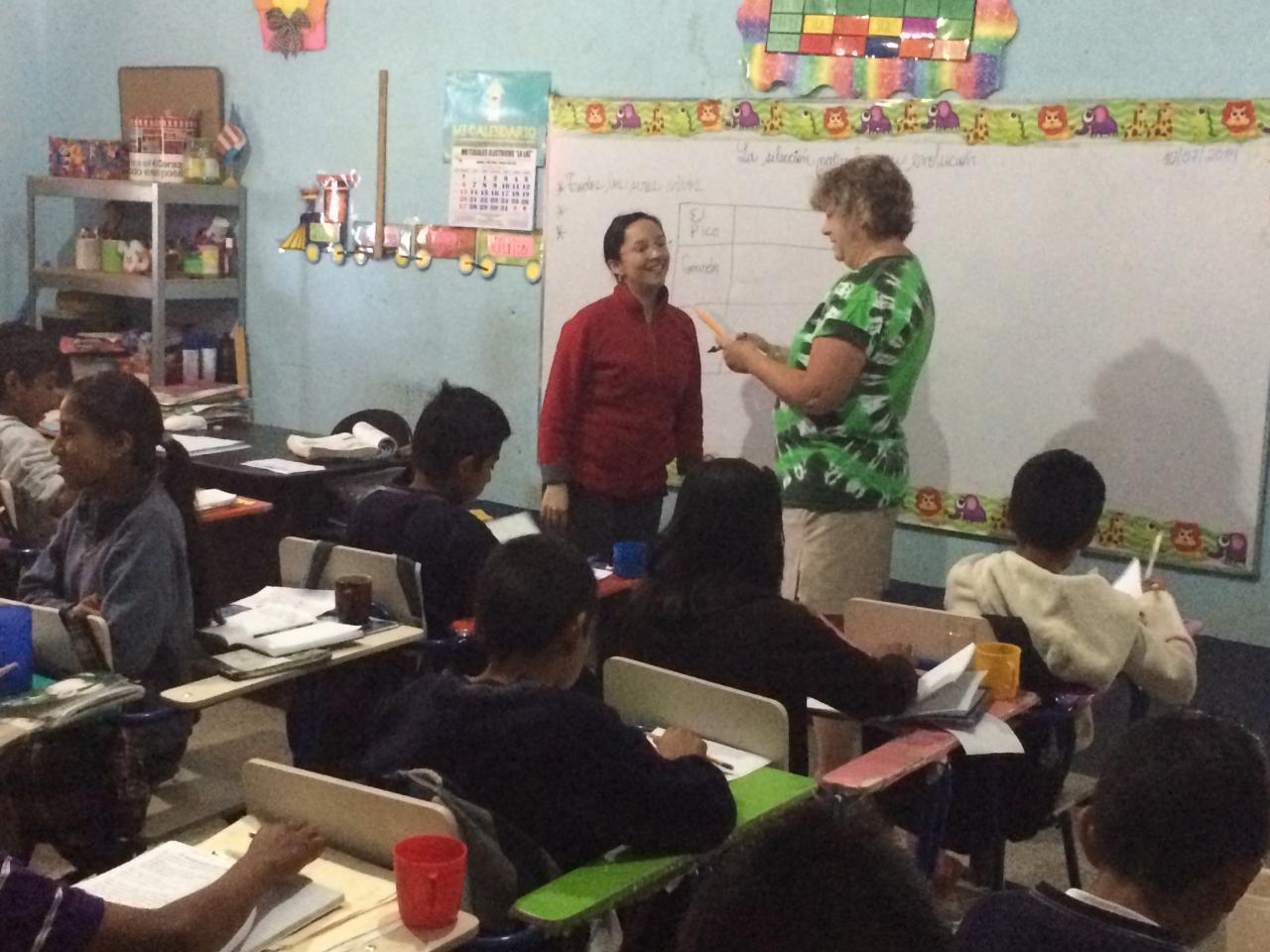

Code Switching in Guatemala

“The world is a smaller place than we sometimes think.” One of Mary’s many field experiences was a summer Spanish Language and Cultural Immersion Program to Guatemala in 2014. Naturally, Mary focused on ways to bring her experiences back to her science classroom.

From her journal:

- One coffee tree produces enough beans for one small bag, or 32 cups of coffee.

- Musical instruments were made from conch shells, turtle shells, animal hides and tree trunks.

- Textiles from different regions in Guatemala have different patterns, and warmer climates near the ocean use more white fabrics for their clothing.

- There are 33 volcanoes in Guatemala. One is huffing and puffing in the distance.

Mary taught a 6th grade class a lesson on natural selection, in Spanish. She struggled with the language barrier, and recognized that the students who were trying to learn English struggled with verb tenses, just as she was doing in Spanish. There was a lot of code switching, blending Spanish and English to get points across. Getting jostled by crowds in an open-air market, taking photos with chickens on a bus, and roasting marshmallows in the vent of a caldera were all experiences this Colorado girl will never forget.

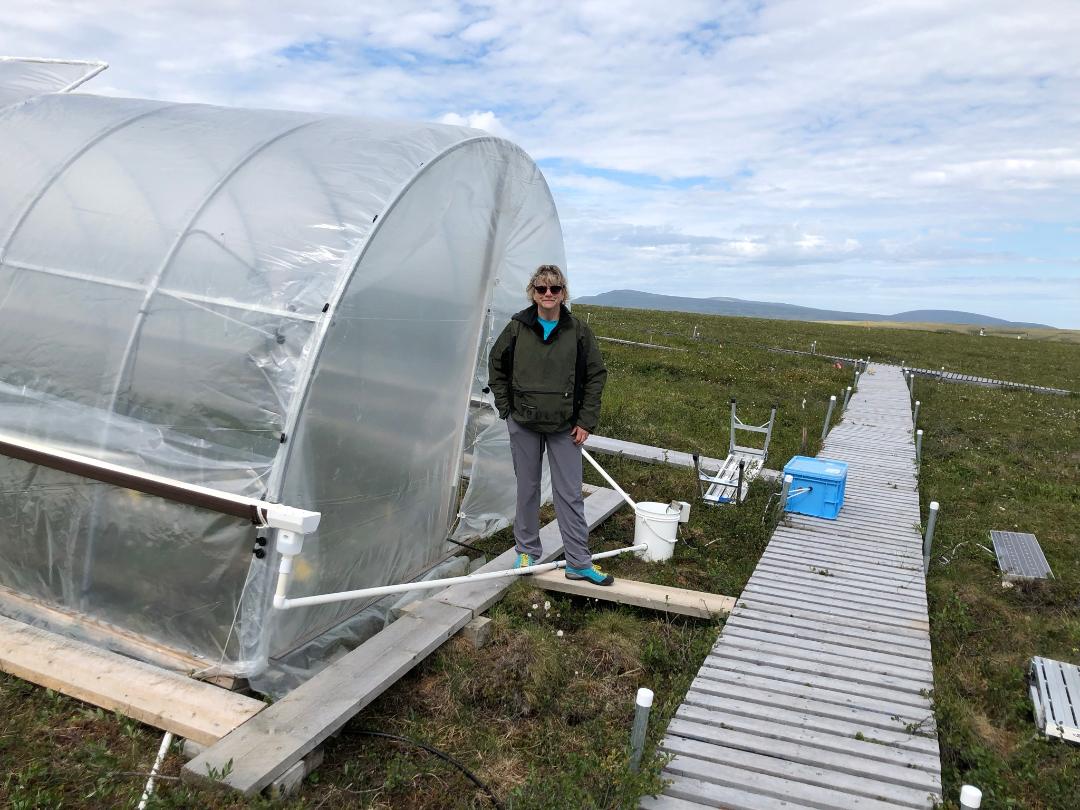

Toolik, Alaska

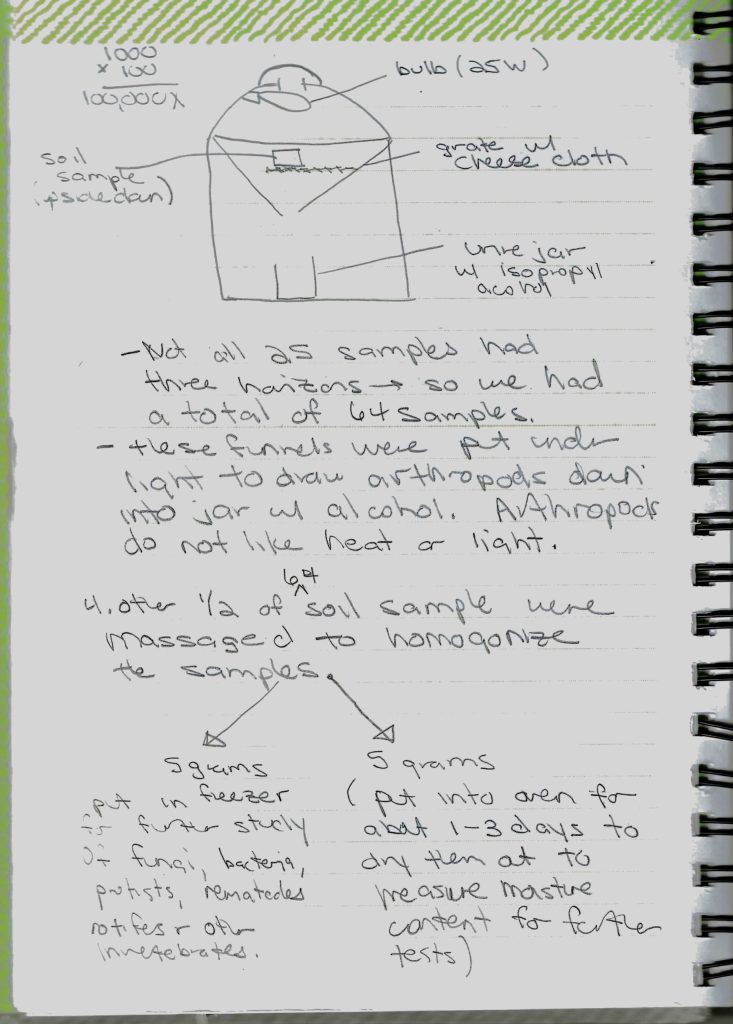

In a Research Experience for Teachers (RET) with the Natural Resources Ecology Lab at CSU, Mary did phenology and soil studies at the Long-Term Ecological Research Station in Toolik, Alaska in 2016.

- Mary taught a fire ecology unit in her middle school classroom, and was interested in how fire affects the arctic ecosystem.

- She participated in soil studies in Alaska to compare carbon and nitrogen in severely burned, moderately burned, and unburned soil.

- She learned about photo posts which allow researchers to take pictures of the landscape at various times of the year from the same location and do comparative analysis. This aids in phenology studies of seasonal latitude changes as well as long term changes.

- Her science notebook allows her to recall details, share with her students how “real scientists” keep notes, and question and reflect on her own learning.

Bringing it Home

“My science travel experiences have kept my science teaching invigorated.” Mary taught at Cache La Poudre Middle School in LaPorte, Colorado for decades. The school includes property that borders the Poudre River, and is an ideal outdoor classroom. “I can take kids to the river anytime!” she remarks. She encouraged teachers in her building to use the river for any discipline, not just science. Her department developed lessons using the river for chemistry, physics, geology, biology, and ecology. Taking kids outside made science relevant and real. She used her field research experience to help her students do their own field research. Students conducted site analyses, used field notebooks, collaborated with others, used photo posts and game cameras to collect visual data, used dip nets, dichotomous keys, and probes to collect quantitative data. Students would refer to data collected by students in years past, mimicking the Long-Term Ecological Research that Mary participated in at Toolik.

Some teachers are concerned about taking students outside. One thing Mary Richmond was able to do at her school was to get teachers comfortable keeping an entire class engaged in learning while staying safe in an outdoor setting. Even though she is now retired, she hopes to continue to help teachers get kids outside, take field trips, and find ways to use their school grounds and surrounding neighborhoods as outdoor classrooms.

Field Work in a Pandemic

“The important thing is to get kids outside!”

How can you do this when learning is remote and on a computer screen? Mary Richmond figured out ways to make it happen during the pandemic. Phenology studies became one way for students to share data by taking pictures of the plants in their yards and posting them throughout the year. She played “Nature Bingo” where students had to explore their neighborhood taking pictures of things on a class list, and then sharing their findings by playing bingo together on their computer screens. Mary continues to ask her kids to get wet, get dirty and get excited about science!

Go For It

Do you want memories of science field experiences around the world when YOU retire? If you are a researcher, consider offering an opportunity for teachers to join your team in the summer. If you are a teacher, start looking for research opportunities now.

- Take the plunge with a NOAA research vessel.

- Go out on a limb in a rainforest in Costa Rica.

- Grow with the maize in Mexico.

- Go ape with gorillas in Rwanda.

Stay fresh with field work.