NoCo Science Education Blog: The Power of Learning Outdoors with Carol Seemueller

by Victoria Jordan

“We stopped doing field research at Cathy Fromme Prairie because the students had too many rattlesnake encounters,” Carol Seemueller explains. “We moved to other natural areas around the city.”

Carol Seemueller, recently retired biology teacher who spent most of her career at Rocky Mountain High School in Fort Collins, made a habit of taking all of her classes outdoors for authentic field experiences as much as she was able. “Kids would light up, and they were so passionate about learning when they were doing science outdoors,” Carol says.

River Watch

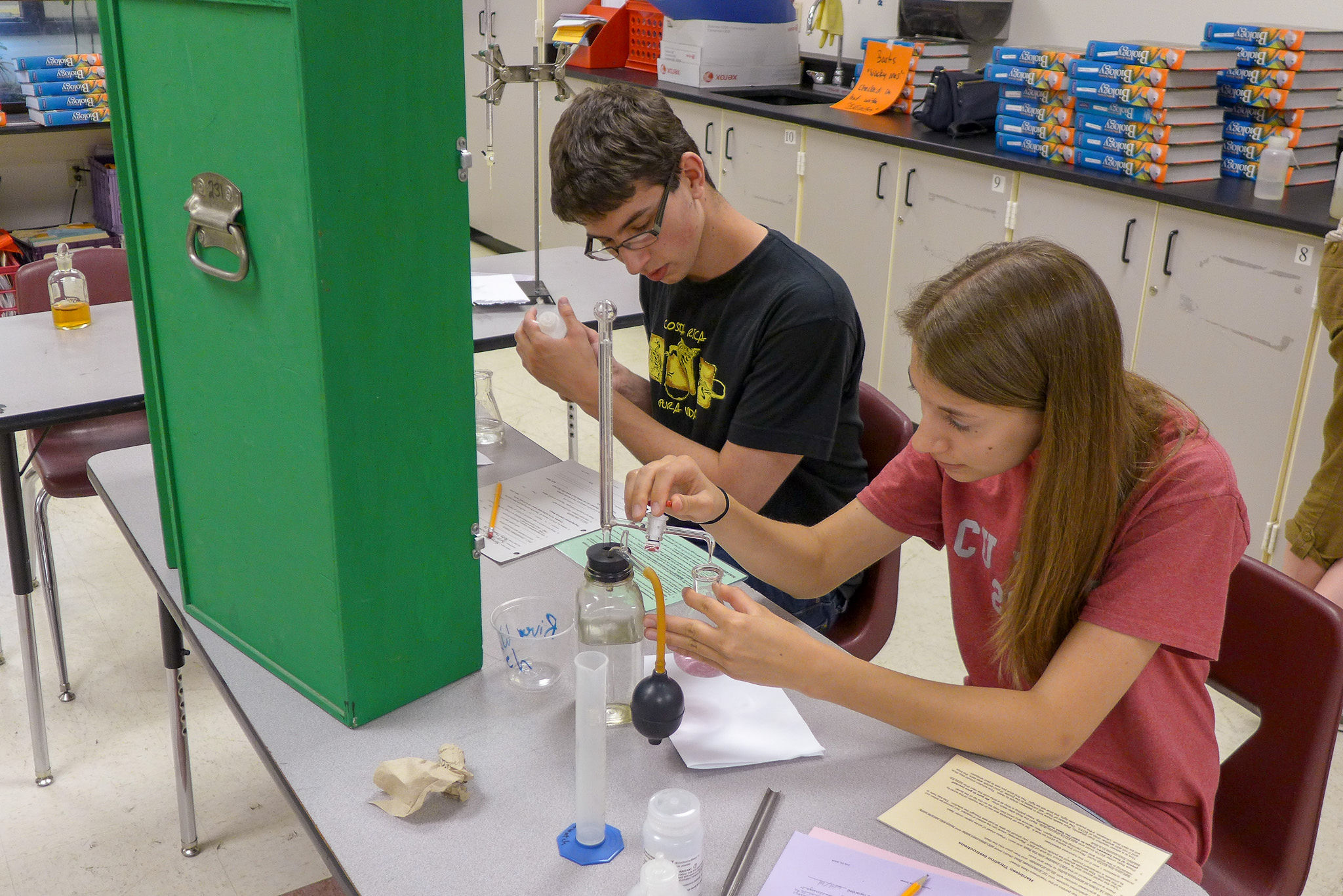

From 1996 through her retirement in 2016, Carol’s students participated in River Watch, a statewide volunteer water quality-monitoring program operated in partnership between River Science and Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW). This citizen-science program works with voluntary stewards to monitor water quality and other indicators of watershed health and utilizes this high-quality data to educate communities and inform decision-makers about the condition of Colorado’s waters. Carol had a team of River Watch students every year that went with her to two locations monthly to collect data, one site on the Poudre River in Fort Collins, and another along Spring Creek near the high school. She and the students created wonderful memories together by exploring outdoors.

“One time, the students wanted to do a full moon water sample,” Carol says. “I went along with it! Why not? We had a blast in the dark trying to follow all the protocols to collect the water while laughing and splashing under the full moon. We got back to Rocky at 10 pm, and still had to process all the samples. The kids talked about that for months. Through River Watch, I created vibrant relationships with dozens of students.”

“We had a collection day scheduled shortly after the big flood in 1997. When we got to Spring Creek, it was unrecognizable. The students were so excited to collect the water that we couldn’t resist. I kept them safe, but a city worker reprimanded us for being too close to the floodwaters. “I know those students will never forget the oily sheen on the water’s surface, the dramatic change in substrate, the missing gravity bridge.”

In 2011, the students collected invasive bullfrog tadpoles and brought them back to the classroom to raise. Carol infused lessons on this species into her biology class because of the curiosity of her River Watch kids. After the High Park fire in 2012, there was so much ash in the Poudre River that it really impacted their water quality data. Then, following the post-fire flood in 2013, there were no more bullfrogs in the river!

“Students were curious about things when they could study patterns and ask their own questions. The High Park fire created a lot of interesting questions. Comparing two water sources always produced questions! When students ask their own questions, they dig deeper into the subject and their curiosity inspires learning.”

Learning Outside

“When students read about something, they might learn something about it. However, putting your hands and feet in it, feeling it, and walking with it creates personal knowledge through experience and brings a passion to the learning that will never be forgotten.”

Carol explains that it is much easier to create bookwork lessons than it is to manage authentic science experiences whether they are in-class labs or outdoor field work. Additionally, there are so many barriers these days to getting kids outdoors that teachers often give up. Between composing a permission slip with all the legal requirements included, and then collecting them back from every student; the near impossibility of getting a bus at the times they are needed, and then finding the money to pay for them; figuring out a way to cover classes or students who are not attending the field trip; pushback from other teachers, parents, or administrators who don’t understand the value of the field trip, it’s a wonder we get kids outside at all anymore! Carol managed to do it consistently.

“Field work feeds the teacher’s soul!” Carol exclaims with excitement. “The payback is tremendous! Barriers fall away when I feel the students’ excitement during the trip, and hear kids talking on the bus saying things like, “Why don’t we do this more often?”

Finding Opportunities

Carol was always looking for new opportunities to learn herself, which led her to new opportunities for her students. During the Chronic Wasting Disease outbreak in Colorado mule deer, the Colorado Division of Wildlife offered a few teachers the opportunity to assist with field research, and Carol jumped at the chance. Feeling the blast of helicopter blades overhead as a mule deer in a net was lowered gently for inspection by a wildlife veterinarian was an adrenaline rush she won’t forget.

Later, her biology students got to participate in a wildlife research simulation on the CSU campus by taking fake blood samples from a mule deer model with a CSU graduate student teaching them the protocols. Because the field experience was so powerful, the students were excited to learn and apply statistics and radio telemetry through hands-on activities at CSU.

“Once people know you like to do extra things, they reach out to you,” Carol says. “I had a lot of people contacting me through the years asking if I wanted to join this or that research.”

Through a GK12 grant opportunity, Carol had 4 graduate researchers from CSU paired with her classes. She traveled to the Arctic for summer research through this connection, and her students were benefitting by having the researcher in the classroom. One of the grad students helped her develop field research protocols for studying plants, insects, and soil nitrogen which she implemented with her classes in a microhabitat study. One parent wrote a note, “My daughter won’t be going because she is afraid of spiders.” Carol managed to convince the parent and the student that she should attend, and through exposure and experience, the student’s fear of spiders was at least abated if not overcome.

“Knowing who students are and developing relationships with them was the most important aspect of my teaching,” Carol claims. “It was easier to develop those relationships when we had authentic experiences together.”

“I found new things to involve myself in, often paying my own way for new opportunities.” For example, Carol took herself to the University of Pittsburgh for three summers to learn how to be a phage hunter! Tuberculosis bacterium are becoming drug resistant, and bacteriophages are the next idea in countering this disease. She was able to train her students to look for and isolate new phages from Colorado soils, and her AP biology students sent several novel phages to contribute to the bioinformatic genomic database at the University of Pittsburgh.

Collaboration

“There is power and possibility in collaboration.” Carol has always been inspired by other teachers and her students. Her partnerships in her school and her community were what kept her ideas flowing. “I was able to endure as a teacher because I was sharing the challenges with other teachers. I never did any of this by myself!” Carol lists dozens of names of those who shared her challenges, her joys, and her students.

Community connections were important resources for Carol. In 1994, she took the Master Naturalist training through the City of Fort Collins. She became passionate about birds, and saw opportunities for more field work with her students. She was good at grant writing, and procured a classroom set of binoculars and bird books as well as bus money for field trips. Her biology classes learned bird identification, and during spring migration they would go out together and look for birds. Carol still participates in the Audubon Christmas Bird Count.

“I still have former students come up to me in the grocery store and tell me which birds they saw this week!”

Connecting her high school students with elementary schools was another collaboration she enjoyed. “When kids teach kids, the happiness is infectious!” Her anatomy/physiology students would teach a heart or lung dissection to elementary students every year. Elementary teachers would contact her with the news that the school PTO had already set aside the money for the hearts for the next year right after her students completed the lessons.

Another collaboration was when her high school students designed and built traps for mountain pine beetles. They brought the traps to a tree farm up Rist Canyon and worked with Stove Prairie Elementary students to set the traps and collect the beetles for a field study. Place-based learning is important to Carol. Figuring out what is happening in our own backyard helps us to act locally to solve important problems. Making science real usually involves looking and wondering close to home.

Continuing Learning Outdoors

One of Carol’s students, Cassia Rye, entered an essay contest. The prize involved the student and teacher getting to take SCUBA lessons and spending time at the underwater research station Aquarius in the Florida Keys. Carol had never considered diving, having a bit of a fear factor. However, when Cassie won, Carol could not back down! The tables were turned. The teacher became the student. They dove together in the Keys, and even met three NASA astronauts 60 feet below the ocean on the Aquarius. A new outdoor experience led to even more underwater exploring that continues to this day.

Just because Carol is retired from classroom teaching does not mean she is retired from teaching! Carol participated in Monarch Watch with her students for 20 years, with her students raising caterpillars in the classroom. Students could observe how hormones change caterpillars into butterflies just as they move humans through puberty. “Peoples’ appreciation grows as they wonder about things. Studying monarchs is an interesting way to gain that wonder and appreciation for our planet.” Now, Carol has 12 families in her neighborhood participating in Monarch Watch! Together, they plant milkweed and raise monarch caterpillars. She continues to spread the love of science and is helping to create life-long learners in her community.

How can you give your students authentic field experiences?

What opportunities have you found lately to expand your knowledge?

Who can you collaborate with?

“Life is eternally fascinating! Challenge yourself!”

-Carol Seemueller

NoCo Science Education Blog: Creating Student Researchers with Dr. Paul Strode

By Victoria Jordan

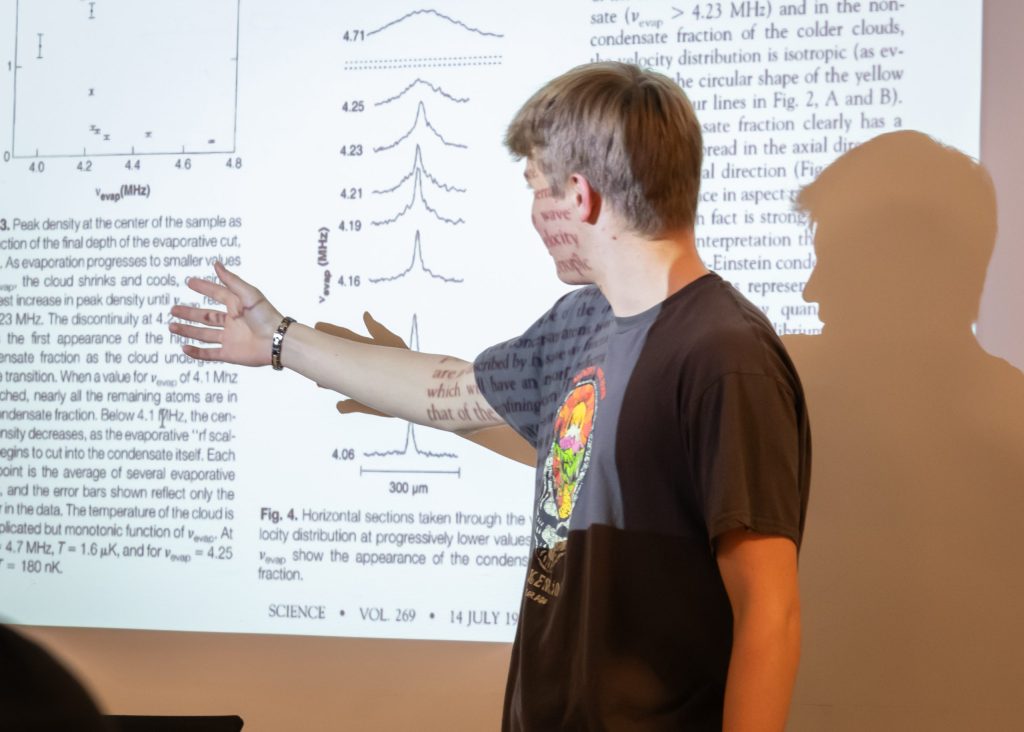

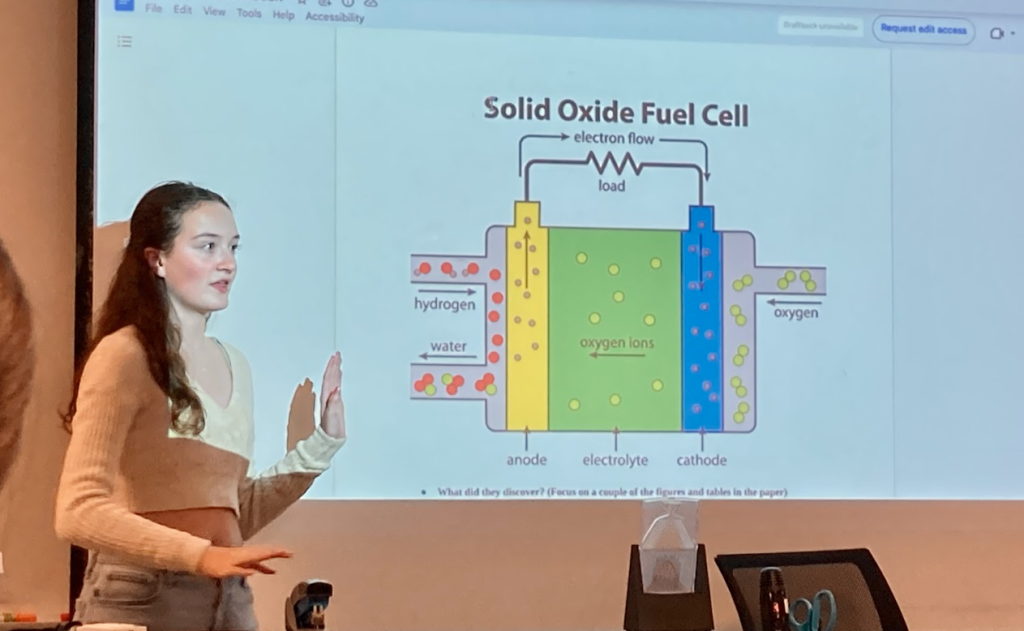

“We tried hard to understand the Faraday reaction in this journal article, but we aren’t sure how that affects how much the system will reduce nitrogen oxides in diesel emissions,” explains Anna Kumar and Lucia Noel to an attentive classroom of fellow high school students. “We want to find a way to change everyday materials to make them more efficient and eco-friendly.”

Questions abound following the students’ presentation of a scientific paper to their classmates.

“What are the big take-aways from this paper that will assist you in your research?”

“Is there an environmental aspect of this research that could have a negative future impact?”

“Why are there three Y-axes on the graph?”

“What was it like for you to try to understand this paper?”

Students in Dr. Paul Strode’s Science Research Seminar (SRS) class are learning how to become scientists and engineers in their own right. Dr. Strode explains, “Fundamental knowledge needs to be understood, but for success in research you must learn specific techniques, targeted concepts, and explicit details about your topic that are not part of a regular curriculum. I don’t think my students fully grasp how ‘not normal’ this class is!”

Dr. Paul Strode earned his teaching license in Indiana while majoring in biochemistry at the small college in the town where he grew up. He taught high school near Seattle, Washington, for several years before moving to Illinois for his Ph.D. in Ecology and Environmental Science at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana. In 2004 he and his wife, Dr. Sarah Zerwin, and their then 1-year-old daughter, Jane, moved to Boulder, Colorado, for her Ph.D. in English Education. Paul and Sarah now both teach at Fairview High School in South Boulder! In all of his biology classes, but especially SRS, Paul’s goal is for his students to learn to think, talk, and write like real scientists. “If they internalize that, when they talk about their projects to others, they will be understood, and they will be on their way to a future STEM career.”

Let’s see how Paul makes this happen!

Think Like a Scientist

Paul engages students by figuring out what makes them curious about the natural world. “I meet the students coming into next year’s class in May before school lets out for the summer. I give them an assignment to explore science topics over the summer to hone in on their interests. They each pick a non-fiction science book to read over the summer. Then, we have a book talk in September when school resumes, and they get to hear about more topics than perhaps they explored on their own.”

Thinking like a scientist involves understanding process and product. To that end, Paul doesn’t use a textbook in his classes. Instead, he pulls current scientific journal articles, and has students dive into them. They study the methods and materials used in the papers, digging through the technical writing to find details about the process of conducting research. They also compare a variety of papers from different journals on the same topic to answer the question, “What are common elements of the scientific process?”

Data and error analysis skills are essential in science so Paul breaks the class into 4 teams. Each team is given a research paper that uses a different statistical analysis technique; for example: t-Test, ANOVA, or correlation and regression. Students work together to learn the tests and then teach them to their classmates. “Making sense of data allows his students to not only practice science authentically, but also allows them to become constructive, concerned, and reflective citizens,” Paul says. To help with data analysis he has written a 70-page guide for high school students on statistical analysis called, Making Sense of Data: A Statistics Survival Guide.

Talk Like a Scientist

Teaching students how to think like a scientist is challenging. In the process, they begin to understand how to talk like scientists because they are using journal articles with partners and teams and discussing scientific processes and products. Then, they present their findings to the class while receiving real-time feedback from Paul and their classmates.

Scaffolding the learning is key. At first, students are daunted by the technical writing in journals. As they dissect each article, however, they build confidence and begin to see patterns. Paul brings in guest speakers who are professional scientists and engineers and also former students who are pursuing degrees in STEM, and the students experience how scientists talk about their research. Listening to real experts is inspiring because of their enthusiam for their subjects is contagious!

Write Like a Scientist

“The high school lab report does not exist in STEM fields,” Paul laments. “Is it necessary for students to write so many lab reports in their class for an audience of one, the teacher? Instead, students could be spending their time writing research questions that can be tested, differentiating between predictions and hypotheses, designing their own experiments, keeping a science journal, analyzing data, and maybe writing two technical papers styled after professional journal articles.”

Early in the semester in his Science Research Seminar class, students have narrowed down their research topic, and work to generate testable questions, create hypotheses, and begin to think about experiments. At each step, they write as though they are submitting their research to be published in a journal. Throughout this process, students contact scientists and engineers that might be willing to serve as a mentor. Many of the potential mentors have worked with Paul’s students in the past and have learned to trust that Paul has prepared the students to think, talk, and write like scientists, and the students are eager to begin.

Dr. Ryan Langendorf is one such mentor. He has been working with Paul’s students since 2014, and says, “Mentoring gives me such hope for our future. These young people develop fun projects that allow me to grow through collaborative discovery! Paul has an insane amount of success with his students. He maintains his composure through challenges and is relentlessly calm. I wish there were more Pauls out there!”

Paul stresses to his students, “If you can’t write in science, it doesn’t matter what you’ve discovered or what new knowledge you have to share; no one will publish it!” Paul spends hours giving feedback on writing, coaching students through problems, and helping them find resources. One of the most unique aspects of Paul’s class is that the students conduct their research on their own time, not during class. Class time is for honing their scientific communication skills. “Often the most difficult thing for students to write is their introduction because it requires them to weave together numerous previously published facts and ideas about how the natural world works. The students must be creative and hook the reader while being concise. By the time they are writing their technical papers, they have seen so many professional papers that they can model their writing off of others.”

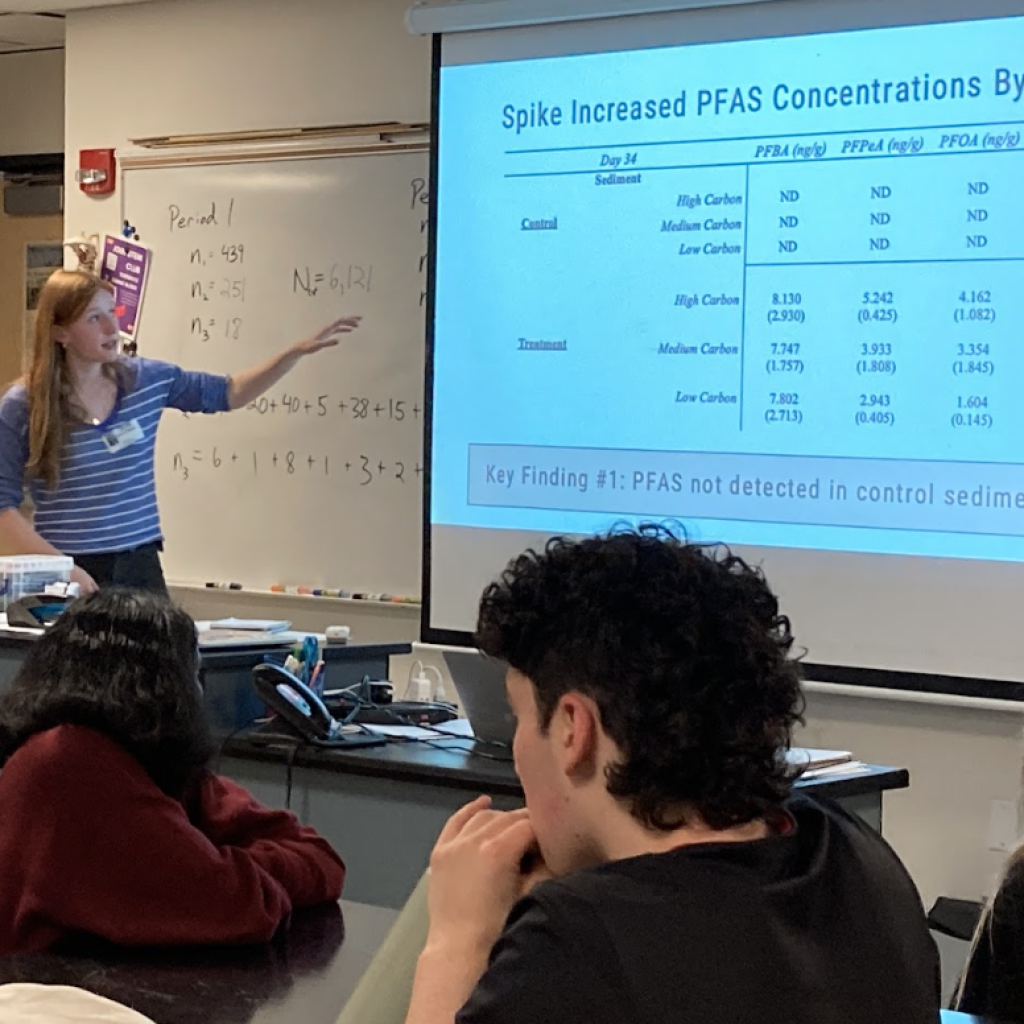

Results

Paul’s students have many outlets for publishing their research to an audience that goes beyond the single classroom teacher. All of them submit their research to Regional and State Science and Engineering Fairs. Some students choose to submit their work to the national Journal of Emerging Investigators. And, at the end of the school year, they present their work at a symposium that Paul and his colleagues at several other District high schools organize. There students share their research with other high school students, teachers, and parents. Paul also has recently started publishing a Fairview High School Journal of Science Research as well, and includes all the students’ research papers professionally formatted to honor their year of dedicated research.

“The students’ research projects are not for an audience of one, the teacher. Everything they do is for a bigger audience, whether it be presenting to their peers or to judges at the Science and Engineering Fair. The end goal is not a grade for the class or even a ribbon. The end goal is much bigger: self-fulfillment and authentic experience in science,” Paul explains.

Over the years, Paul’s students have received top awards at their Regional Science and Engineering Fair and also at the state’s Colorado Science and Engineering Fair (CSEF) run by the Natural Sciences Education and Outreach Center at Colorado State University. Many of his students have had the highest honor of presenting their work at the International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). He is proud of the continued work that many of these students are doing. Many people are surprised at the types of research his high school students are doing in chemistry, physics, biology, microbiology, geology, engineering, and environmental science. “When students are motivated and interested in something, we can help them work on the fundamentals, but then we need to just get out of their way!” he claims.

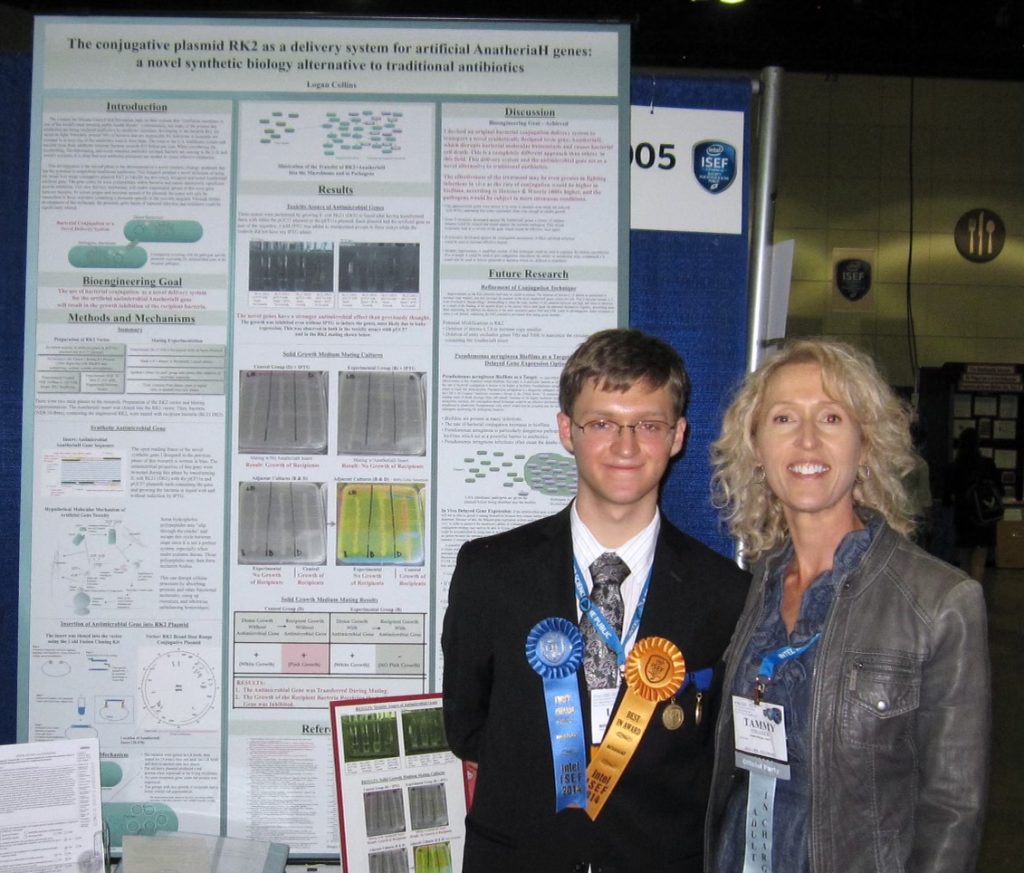

“Logan Collins entered the science fair every year in high school and took the SRS class three times in a row. As a junior his project was awarded Best in Show at both the Regional and State Science and Engineering Fairs and Best in Category at ISEF.”

“At ISEF he also received an award to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden. He is now doing doctoral research at the University of Colorado, but it all started when high school Logan figured out a way to cause a bacterium to take in a plasmid that he designed that kept the bacteria busy making nonsense proteins, eventually killing them. It is a potential solution to antibiotic resistance! Doing research in high school supported by a class with other like-minded students gave him what he needed to find his passion and flourish.”

“Vanessa Haggans studied nutrient availability in tundra plants to determine if nutrients were limiting factors. She went on to Dartmouth College for a double major in economics and environmental science. She is now planning to take her science literacy and research skills to law school.” Vanessa recently returned to Fairview and presented her research to Paul’s students.

“Science is such a broad subject,” says current student, Zachariah Nagle, “that we never get to explore our niche interests. Dr. Strode changes all that!”

“Dr. Strode gives us support, helps us work through difficult material, and guides us so we have a clue how to do science,” adds Pragnya Pilli.

Imagine: How would the world be different if every student was at one time a researcher who learned how to think, talk, and write like a scientist?

If you are a student, how can YOU start a research project? If you are a researcher, what can YOU do to mentor a student? If you are a teacher, what can YOU do to develop lessons in your classroom to teach students how to think, talk, and write like scientists? It’s worth the effort!

Please visit Dr. Paul Strode’s amazing website at: https://fah.bvsd.org/about/staff/science/paul-strode

Find information about the Colorado Science and Engineering Fair here: https://csef.natsci.colostate.edu/

and the Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair here: https://www.societyforscience.org/isef/